A History of Nudity in Paganism, Wicca and Witchcraft

Guest Blog by: Liam Cyfrin and Caroline Tully

A Fig Leaf of our Imagination

There are countless quirks about humans, but one of the real doozies is that most are confused, divided and downright ditsy when it comes to their own physical nature. To millions, the human body in its natural state is embarrassing, shameful, indecent or undignified. Its exposure provokes hostility, fear, nervous laughter or mockery. It threatens social standing, challenges order, infringes laws and is often punished with a severity bizarrely incommensurate with the offence.

The really odd thing about this is that it’s not generally considered odd at all. The necessity of concealing bits of the human body is taken for granted in precisely the same way that the need to provide animals with trousers isn’t. And they call Pagans irrational and superstitious.

Witches, Druids, and Pagans of many other species tend to be among the minority who don’t buy into humanity’s alienation from its unembellished form, recognizing this to be both symbolic and symptomatic of a desperately unhealthy estrangement from nature. Partly for that reason, as you’re reading this, several thousand Witches and Pagans around the world will be casting their Circles, wearing no more than they wore in the womb.

Not all Pagans regularly work skyclad – some do when alone but not in shared Circles, many alternate between skyclad and robed workings, and others always work in clothing of some sort – but most respect the practice and consider it a valid element of the modern Pagan tradition. If nothing else, this shows a spirit of determination, given that it is often cited by opponents of the Pagan path as evidence of chronic “up-to-no-goodness.” Acknowledging this, some groups (especially in the US) have chosen to downplay or totally abandon skyclad working. For many in the Old Religion, however, it remains as much a part of the path as such other “unpopular” elements as spell-casting, individual approaches to deity, and the troublesome words Pagan and Witch itself. Let’s consider the lineage of ideas that led to this conclusion.

Much Ado about Wearing Nothing

Those disapproving of ritual nudity often argue that the practice has no significant historical precedent in either religion or magick. Leaving aside the issue of whether this has any (for want of a better word) bearing on the effectiveness of skyclad Witchery, it is true that, although attitudes towards nakedness have varied enormously in different times and places, religions in which nudity is an essential part seem to have been thin on the ground. Paddy Slade, one well-respected Witch with a disparaging, slightly Granny Weatherwax-ish attitude towards nudity as a Wiccan dress option, maintains that “no tribe, primitive or otherwise, goes to meet its God unclothed” (Natural Magick [Hamlyn, 1990]).

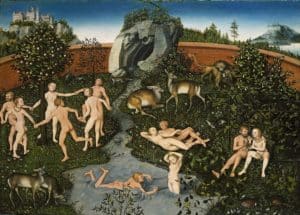

This would seem to be a wee bit of an exaggeration. The idea of ritual nudity is an old one, being found in the ancient cultures of places such as Pompeii, Greece, India, Rome, Persia and Britain. The Mother Goddess of Calcutta in India, Kali, is usually represented as nude and she is said to be Digamba, a Sanskrit word meaning “clothed in Space.” Pliny the Elder, in his Naturalis Historia, records that the women of ancient Britain performed their religious rites in the nude.

Such traditions notwithstanding, Ronald Hutton, Professor of History at the University of Bristol, was initially of an opinion similar to that of Ms. Slade. However, in his appealingly titled essay, “A Modest Look at Ritual Nudity” (included in his Witches, Druids and King Arthur, [Hambledon and London, 2003]), he modified his position in the light of continued research. In that piece, he lists a few historical precedents for Wiccan naked gatherings (generally among minor 14th and 15th century sects, such as the Turlupins of France, the Men of Intelligence of the Netherlands, and the Adamites of Bohemia), before concluding that the Craft “is not unique in this respect, although it is unusual.”

Ritual nudity does, Professor Hutton acknowledges, regularly feature in rites of passage, particularly initiations, which leads him to offer the tentative theory that one of its purposes in the Craft is “to sustain throughout all its workings the intensity and transformative power of initiatory experiences.” He finds it more significant though that, while nakedness in religion is about as common as integrity in politics, nudity in magickal lore and practice is widespread, both globally and historically. For example, there is an old English idea that a woman can be cured of infertility by walking about nude in her vegetable garden on Midsummer’s Eve.

The most casual research into traditional spellcraft and the representation of Witchcraft in art and literature confirms the point, and the often repeated line in Aradia (Charles G Leland, [1899]) exhorting Witches to be “naked in your rites, both men / And women also …” is simply one of the more obvious statements of the principle. In many cases, though, such folkloric mentions of nudity weren’t intended as sociological observations as much as evidence of the depravity of the Witches (or heretics, supposed savages or, a little later, hippies, “ferals,” trouserless animals, etc). Accordingly, they may be no more reliable than the occasionally attendant charges of cannibalism, shape-shifting and broomstick aviation.

Some corroboration, however, might be found in other, less accusative descriptions of sorcerous activities in which nakedness still plays a part. In these instances, the absence of clothing is often just one of several reversals of the normal social order used in the working. Fair is foul, foul is fair, and naked is perfectly normal.

The concept of social reversals remains a force within the Craft. When our sense of ownership of our bodies is challenged by laws or other imposed codes of behavior, reclaiming it can be a source of personal and magickal power. As Australian Witch, Priestess and suspected Elf, Amargi Wolf, puts it: “The breaking of taboo can help put you in a headspace where anything might be possible. Even for those of us who are inclined not to wear clothes whenever we can get away with it on a day-to-day basis, society’s conditioning regarding nudity is a strong force to be played with.”

This mightn’t be exactly how it would have been conceptualized by a 17th century farm girl performing a love spell (yes, the politically incorrect sort, most likely) naked beneath a waxing moon, but she’d still have been aware of being in a strange and invigorating situation in which mundane reality was kept at bay and the possibility of her spell’s bringing results seemed well within the bounds of expectation.

Gerald Gardner and the Bare Witch Project

Skyclad bodies abound in pre-20th century folkloric accounts of spellcraft and divination. They’re equally common in several other major influences on the Craft, such as faerie-lore and imagery and Classical art. It’s nevertheless not uncommon to read that today’s naked Witch exists solely because Gerald Gardner, one of the Craft’s most significant revitalizers, happened to be a card-carrying, sun-soaking, bottom-baring naturist. Likely? Let’s see.

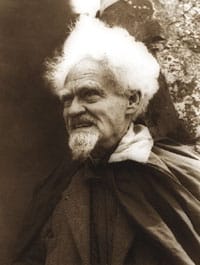

We don’t yet (and may never) know precisely how modern Wicca got started, but we can be reasonably confident that two of the most widely published versions are as full of holes as a very large Swiss cheese sandwich after a drive-by shooting. Version One is the “Unbroken Line” theory, which maintains that Wicca is an ancient Pagan religion that went underground and survived the Burning Times, Spanish Inquisition, English Civil War, Punk Rock and Disco. Version Two is the “Guru Gerald” story, which claims that the late Mr. Gardner pieced together the whole shebang in a prolonged fit of post-retirement restlessness.

While little real evidence has come to light establishing that Gardner actually encountered an active form of the Craft in the 1930s, recent studies strongly suggest that: (a) the revitalizing of Witchcraft was a group effort; (b) several members of that group were already merging folklore, occultism and Paganism before Gardner’s involvement; and (c) another common interest in this subculture, before and after Gardner’s joining in, was naturism.

It now seems likely that it was through membership in naturist organizations that many key players in the magickal revival first met. Consequently, even if we choose to discount earlier Witch-lore and date the skyclad tradition to this era (as we can the Wiccan use of the word skyclad, borrowed from Jainism), we need to allow that it was the product not only of Gardner’s interests, but of those of a small but significant subsection of the magickal community of the time.

If we consider today’s nudist organizations, the more conservative of which still fall over themselves to project an image of utter normalcy (once the dress-code is overlooked), their significance to the Craft might seem strange. In the 1930’s, however, naturism was a new, rather radical and esoteric movement, possessed of a strong spiritual dimension. Its earliest forms in Germany typically embraced a reverence for nature, a longing for the pre-industrial past, and the promotion of physical fitness, often expressed through abstinence, vegetarianism, and exercise regimes that would make the average Tae-bo trainer run for cover. (Much of the movement’s spirituality seemed to slip away in the 60’s and 70’s, only to find a new home in various nude-friendly offshoots of hippiedom, from Australia’s Down to Earth Co-op and Osho communes to emerging Pagan organizations such as the Church of All Worlds.)

In Gardner’s time, naturism was becoming a little worldlier but still attracted many artists, poets, bohemians and occultists. Among his naturist contemporaries were: several of his original co-Coveners, including (probably) his initiatrix (probably) Edith Woodford-Grimes; Ross Nichols, founder of The Order of Bards Ovates and Druids; Harry Byngham, a major Pagan influence on the already Pagan-ish Order of Woodcraft Chivalry; poet and former Crowley associate, Victor Neuberg; and possibly even Dion Fortune, whose Fraternity of the Inner Light owned property at the Bricket Wood nudist club was frequented by Gardner and Nichols. (For more on this, see Philip Heselton’s Gerald Gardner and the Cauldron of Inspiration [Capall Bann, 2003].)

So linked were naturism and Paganism at this time that it became a standing joke in England to mix the metaphorical and literal senses of the expression “sun-worshippers” when talking about nudist venues. Even as late as 1984, the male lead in a naturist promotional film called Educating Julie facetiously warns his girlfriend about visiting a sun club, claiming “They worship these strange sun gods and have ritual dances in the woods” (a suggestion later labeled as “daft” by a club member).

Attempts to reunite the naked and the sacred weren’t pervasive in the magickal community of Gardner’s time, but they were an influential undercurrent. Gardner emphasized the idea’s importance within the Craft – as Byngham did in his area of Paganism, and Fortune and Nichols didn’t in theirs (although Nichols’s successor, Philip Carr-Gomm, champions skyclad Druidry on the Order’s website and is the author of the excellent A Brief History of Nakedness [Reaktion Books, 2010]). But to claim that old Gerald introduced the concept to his community is a little like suggesting that Norman Lindsay introduced the cheerful, nude-cluttered and defiantly Pagan imagery of his etchings to the world of art.

In the end, “Gerald made us do it” arguments against the use of skyclad ritual become unraveled when they take into account that universal quality of Witches: their fondness for making up their own minds. Most Wiccans have, for example, long since jettisoned the endless binding and scourging that swamped Gardner’s early rites. Ritual nudity, however, retains its currency. Robes, costumes and street clothes are more common at Craft gatherings than they once were, as the Craft takes on open Circles, rituals in public places and so on, but the naked Witch is far from being an endangered species.

That suggests the practice just might have its uses.

Read Part Two: Why the Skyclad Tradition Continues!